BALEARIC LANGUAGE

Sumario

- 1 THE BALEARIC AND THE CATALAN ARE NOT THE SAME LANGUAGE

- 1.1 Linguistic structure of the Spanish, the Balearic and the Catalan. A comparative and Philological study.

- 1.1.1 Cultural bases of the national-catalanism in the Balearic Islands.

- 1.1.2 Opinions of relevant persons in the cultural world.

- 1.1.3 List of grammars and dictionaries of the Majorcan or Balearic language.

- 1.1.4 The first Catalan grammar accepted by the Institut d'Estudis Catalans

- 1.1.5 Linguistic conflicts in Catalonia before Pompeu Fabra. XXth century.

- 1.1.6 False historical grounds of the supposed repopulation of the Balearic Islands with Catalan people.

- 1.1.7 Romance linguistic landmarks previous to Jaime the First.

- 1.1.8 The Spanish, the Balearic and the Catalan languages. A comparative philological study.

- 1.1.9 List of expressions with the same meaning.

- 1.1.10 LINGUISTIC STRUCTURE

- 1.1.11 Phonologic, morphosyntactic and semantic.

- 1.1.12 Phonologic system.

- 1.1.12.1 Balearic syllabic subsystem of double consonants.

- 1.1.12.2 Balearic syllabic system of consonant groups.

- 1.1.12.3 The Catalan syllabic system of consonant groups.

- 1.1.12.4 The Balearic accentuation.

- 1.1.12.5 The Balearic language has three types of accentuation

- 1.1.12.6 The diacritic accent

- 1.1.12.7 The Catalan accentuation.

- 1.1.13 Morphosyntactic System.

- 1.1.14 The Dependent morphemes.

- 1.1.14.1 Formation of the Balearic plural (some examples).

- 1.1.14.2 Formation of the Catalan plural (some examples).

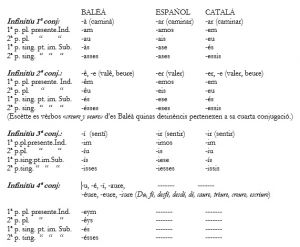

- 1.1.14.3 The verbals conjugations

- 1.1.14.4 Verbal endings

- 1.1.14.5 Balearic tonic (strong) personal pronouns.

- 1.1.14.6 Catalan strong personal pronouns

- 1.1.14.7 Balearic atonic (weak) personal pronouns.

- 1.1.14.8 Catalan weak personal pronouns

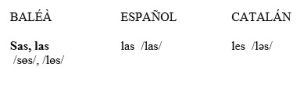

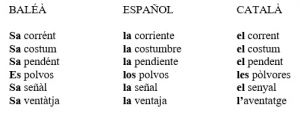

- 1.1.14.9 Different use of gender in balearic, espanich and catalan

- 1.1.14.10 Formation of compound nouns and expressions.

- 1.2 The family Iberian-Italian-Romance language.

- 1.3 The family Iberian-Gallic-Romance language.

- 1.4 Semantics

- 1.1 Linguistic structure of the Spanish, the Balearic and the Catalan. A comparative and Philological study.

- 2 BALEARIC, ROMANCE LANGUAGE

THE BALEARIC AND THE CATALAN ARE NOT THE SAME LANGUAGE

Linguistic structure of the Spanish, the Balearic and the Catalan. A comparative and Philological study.

Cultural bases of the national-catalanism in the Balearic Islands.

From the beginning of the National-Catalanist movement at the end of the XlXth century until our days, more times than necessary has been said and written that the Majorcan or Balearic language is a dialect of the Catalan language; never considering that languages are born and develop in the historical context of the land where they are used, and, since the Balearic Islands is an Archipelago untouched by foreign linguistic influences until the XlXth century, that particular development remained even purer than in other places. This is why those who state the contrary are not true to the linguistic and historical background of the Balearic Islands. A background ignored by the Balearic wisemen themselves, because precisely those who introduced the theory of the Balearic language as a dialect were a group of intellectual islanders under the influence of the political-cultural movement called “La Renaixensa” at the end of the XlXth century, which movement spread the thought of Enric Prat de la Riba, who said:

«...let us do as the English did with their Great Britain, the Empire´s rosebud at its prime, flower of that Empire in the eve of its birth; let us talk of the Great Catalonia, which is not only the County (of Barcelona), or Majorca, or Valencia, but Majorca, and Valencia, and the County, and the Rousillon all together. We are all one, we are all Catalan.” “...and to put that philosophy into practice, we must dominate by the force of the culture, with the help of material force which will help endure the domination; it is a matter of modern imperialism, the integral imperialism of the great strong races of today.»

Alas! And therefore, the most important weapon to unite all these territories will be the imposition of the Catalan language, (because, supposedly, their inhabitants are all of Catalan descent), sanctioned by the intellectuals and backed by the financial power.

The aforementioned Balearic intellectuals acknowledged the lucubrations of Prat de la Riba because, to them, they were was not but an extension of what had been related by the romantic chronicler Ramón Muntaner in the XlVth century, stating that the Kingdoms of Majorca, Valencia and Murcia, had been repopulated with Catalan people who exported the “bell Cathalanesch” to those kingdoms. And of course, they assumed it all as if it were dogma, (never better said, since a great number of those intellectuals belonged to the clergy), without stopping for a moment to think or doubt; and without giving themselves the least chance to investigate and seek rational proof of such aseverations; and in spite of the fact that the Balearic people have never accepted, nor will they ever do, the notion of their being of Catalan descent. Neither will they let their language be called “the Catalan language spoken in Majorca”, Menorca, Ibiza or Formentera. And since, until the end of the first half of the XXth century, ninety percent of the population, not only that of the Balearic Islands but of the entire Spanish nation, were illiterate, it would have been quite difficult for those plain people to refute such satements, their only solution was to remain quiet and go through the mill, to avoid being labelled as ignorants or “gonellistas” (those who made a case for “Majorquinism” without any grounds). To all that we must add that, until the end of the XXth century and, disgracefully, up to our days, social education in the Balearic families has been mainly of a feudal character; meaning that if something is stated by somebody with a post of authority, such statement is dogma to be believed and obeyed unless you want to risk being called an extremist, a fascist or an ignorant, adding to it the snubbing of your fellow citizens, even of your own family. Under such behaviour, those intellectuals had the dough ready to be baked in the furnace of catalanism with the odds on their side. In fact it turned out perfectly for them; it was, of course with the invaluable support of the politicians who passed the Statute of Autonomy in 1983, stating in its third section that the language of the Balearic Islands was the Catalan language. They did it without any historical or philological base, (El Día del Mundo de Baleares, May 19th 2002); because it was the politician Mr. Francisco Conrado de Villalonga, of the obsolete political party UCD, employee of the bank “La Caixa” of Catalonia, and since 1990 General Representative and General Deputy Director of La Caixa in the Balearic Islands, who made the personal decision, (photocopy of his “confession” enclosed) as Cultural Counsellor, that the language of the Balearic Islands should be called Catalan. Furthermore, once the Statute of Autonomy had been passed in 1983, with the only approval of the Balearic political class, a few months later, in 1984, Mr. Conrado withdrew from the political field, since he seemingly thought that he had already done his job. And those politicians did not submit their decision to the opinion of the people of the Islands, although in other autonomies the people were asked their opinion. Nor have they done it in the twenty years that have elapsed since then.

Opinions of relevant persons in the cultural world.

These are the words of the notable Majorcan playwright and actor, the late D. Xesc Forteza, in an interview published in the “Última Hora” daily newspaper on the 7th of July1999:

«...I am an anarchist; no priests, no military, no flags, no religions. They can go on offering me all the money, I will not join any political party. I am proud to say I get on well with everybody, including the bishop. But theatre must never be seen as literary essay. Theatre is the people, and the characters on the stage must talk like the people in the street. Have you realized how they have spoiled our language? The radio professionals on the one hand, and the TV newsreaders on the other hand; to avoid Spanish expressions, they resort to a languaga that will mean the end of the Majorcan original language.” “...Have you read the “Rondayas Mallorquinas” (Majorcan Nursery Tales) standarised according to the rules of the Catalan? If not, you must read them and then you give me your opinion.»

Let us now hear the opinion of D. Miguel de Unamuno, philologist, writer and Rector of the University of Salamanca. During his stay in Majorca in 1916 (“Andanzas y visioness españolas”. Miguel de Unamuno, 1916) he said:

«...the reader must understand that I am reading more than the some half dozen books I brought with me, but the greatest part of my readings is in Majorcan.Curiosity of a philologist. Wherever I go, I like to read in the language of the country; in Portugal, for example, I hardly read but in Portuguese, and here I read in Majorcan.Taking good care that it is Majorcan not Catalan.

(...) However, Majorcan writers tend to write, not in the live language of their country, but in Catalan. Here, writers and intellectuals tend to be Catalanist rather than Majorquinist. The great poet Juan Alcover, after having written verse in Spanish for a long time, did not go back to his mother tongue, the home language of the city where he was born, but to the Catalan, a language that has not a smaller number of conventionalities than the official Spanish language. Naturally: Majorcan writers who did not find the public they sought when writing in Spanish; and in fact, some of them, like Juan Alcover, who did not get the praise they deserved, when the Catalan language revival was reaserted and spread, resorted to that (the Catalan) language. But I have decided to read in Majorcan, starting with the typical “Aguafuertes”, published in 1812 by the late D. Gabriel Maura, the elder brother of the renowned politician D. Antonio Maura, with an introduction, in Spanish!, written by the Catalanist Juan Alcover.

As an effort and an act of gallantry, a Majorcan presbyter, D. Ildefonso Rullán, M. A. in Philosophy and Letters, published the first translation of El Quijote into the Majorcan Language, published in Felanitx in 1905-1906.

But I must tell you again that this issue of the Majorcan language and literature, of such noble ancestry and glorious tradition, dates back to the times of the blessed Lulio.»

Or let us see the opinion of D. Torcuato Luca de Tena writer, director of ABC daily and member of the Royal Spanish Academy, in an interview published in The Day of the Balearic Islands in September 1985 said:

«It is false that the Catalan Language is the origin of the Balearic and the Valencian languages. (...) The Balearic and Valencian cultural expressions are much older than those of the Catalan.»

And let us see the opinion of D. Dámaso Alonso philologist member of the Royal Spanish Academy, in an interview published in Las Provincias Newspaper in july 18, 1982 said:

«The Valencian and Balearic / Majorcan languages are more than 300 years older than Catalan.»

List of grammars and dictionaries of the Majorcan or Balearic language.

To the words of D. Miguel de Unamuno and D. Torcuato we shall add that D. Juan Fiol published what we suppose was the first grammar of the Majorcan language in 1651; D. Miquel Reus published another grammar in 1694; D. Antonio María Cervera published another grammar in 1812; and another grammar was published in 1835 which was studied at the schools of the island, and on which base authors such as D. Gabriel Maura developed further works. This grammar was revised and republished by its author D. Juan José Amengual in 1872.

Dictionaries worth mentioning: Don Antonio Figuera, a monk who had left his order, wrote a “Mallorquí-Castellá” dictionary in 1840 at the behest of a rich family from Muro, Majorca. In 1858, Don Juan José Amengual, author of the last two grammars, published the first volume of his Majorcan-Spanish-Latin dictionary. He published the second volume in 1872. A book by Don Damiá Boatella and Don Matías Bosch was published in 1889. It won an award at the International Fair of Barcelona, and was declared apt for academic purposes. Its title was “Enseñanza Práctica del Castellano en base a la lengua Mallorquina”, (“The Teaching of the Spanish Language, an Approach from the Majorcan Language”). It includes a most extensive Majorcan-Spanish vocabulary. To widen that background, it must be added that the edition of the “Rondayas”, (short popular nursery tales), written in 1895 by the Archduke of Austria Don Luís Salvador, were written in Majorcan; and the translation of the Quixote into the Majorcan Language by D. Ildefonso Rullán in 1906; not to mention the works of D. Gabriel Maura, and of authors like D. Manuela de los Herreros.

The first Catalan grammar accepted by the Institut d'Estudis Catalans

However, it is not until 1913 that the “Orthographic Rules” of the Catalan language is published, written by Don Pompeu Fabra. Later on, in 1917, the same author published the “Orthographic Dictionary”. And it is not until 1918 that the first “Catalan Grammar” is published, being subsequently accepted by the Institute of Catalan Studies. That is only 267 years after the publication of the first Majorcan grammar that we know of. And in 1932, fourteen years later, they publish the “Dicccionari General de la Llengua Catalana”, (General Dictionary of the Catalan Language).

Meaningful, is it not? Why? And very simple: Grammars are the zero milestones, the date of birth of a language.

So we can not talk about the French language until the XVth century, when its grammar was published. Neither can we mention the Spanish language until that same century; or the German language until the XlXth century, when the Grimm brothers published their Grammar of the German Language; or the Italian language until 1860.

Before those dates all these languages were written according to each writer´s free will and knowledge; we know well that every writer had his or her own rules; rules which only the writer considered as such and which in most cases were but orthographic nuances.

Linguistic conflicts in Catalonia before Pompeu Fabra. XXth century.

Things were more complicated in Catalonia, though, because in the middle of the XlXth century some writers affirmed that they were writing in Provençal whilst others said that they wrote in Lemosin, of which we have palpable evidence in the words of the illustrious Don Carles Aribau who, in his poem “Oda a la Patria” (published in the newspaper from Barcelona “El Vapor” on the 24th of August 1833) says that he speaks, writes and prays in Lemosin. Further that, the doctor of Romance languages in Grammaire des langues romanes, Paris, 1890, p.13 says:

«... the Catalan, which is merely a dialect of Provence ...»

And Mr. Marti de Riquer i Morera, Ph.D. in Romance Philology, in his book: "History of Catalan literature", BCN - 1964, p.21, says (sic):

«La literatura trovadoresca, en el seu prop sentid, és l’escrita en provençal…/ …els primers poetes catalans (sigles XII i XIII) de personalitat i nom conegut que escriviren en una llengua romànica, ho feren en provençal…»

«The troubadour literature in its own way, is written in Provençal language. the first Catalan poets (XII and XIIIth century) and determined personality known name written in a Romance language, they did in Provence.»

Will anyone believe that Aribau and the rest of Catalan intellectuals, (knowing as we know so well their great affection for anything that may validate their identity), that if in those times there had been a Catalan language with its grammar and its dictionary they would not have boasted of having their own language, stating and restating that they spoke, wrote, loved and prayed in Catalan?...!!

The evidence is clear enough; and to seek any pseudohistorical excuses which might explain the existence of the Catalan language would be nothing short os distorting the linguistic reality of that language. As we would be distorting the linguistic reality of the Spanish language if we stated that the “Versos Silenses y Emilianenses”, or the Works of Alfonso the Xth of Castilla, had been written in Spanish.

You may ask; in what language, then, were they written? They were written in Romance, in Spanish Romance. As we have said above, due to the absence of general orthographic rules in those times, each author wrote according to the criteria that issued from his intellectual background.

And, regarding the “Glosas Emilianenses y Silenses”, we must add that, though written in Spanish Romance, they contain verses in the Navarro-Aragonés Romance and in the Basc Language. (Lengua Española. 1º de B.U.P. Ed. ECIR, S.A. 1993)

False historical grounds of the supposed repopulation of the Balearic Islands with Catalan people.

Since it has been proved that there was not any kind of repopulation with Catalan people in the Balearic Islands, then there is no Catalan language either, because there is neither evidence of the repopulation of the Balearic Islands given by the king himself in the “Crónica del Rey Jaime the lst”, nor in the “Libre dels Feyts”, nor the slightest signal of that imaginary fact. Furthermore, all the inhabitants of the city of Barcelona, which was supposed to be the most important city of the Kingdom of Aragon, would not have been enough to repopulate the city of Palma, because in those times Palma was thrice the size of Barcelona, and it was not until the XVlllth century that Barcelona attained the importance of Palma. However, what leads us to the clearest indication that there was not any kind of repopulation in the Balearic Islands is the fact that the Holy Mother Church warned their inhabitants to keep the keys of their homes in their keyholes the twenty-four hours of the day (which thing, amazing to him, Miguel de Unamuno alludes to in the book beforementioned), so that any old christian might enter the house at any time of day or night to check if someone was still secretly following the rites of the Jewish religion.That mandate would not have been necessary had there been a repopulation with Catalans, which is equivalent to old Christians. That requirement became a habit until in the mid XXth century, when thieves mingled with the stream of tourists who landed on the island, and very happy were they (the thieves) when they realised they didn´t need to force the locks of the doors to burgle a house. And anyway, and besides the documented facts, what remains of a Catalan presence are there in the Balearic Islands? Since... we must bear in mind that we are talking about the imaginary settlement of thousands and thousands of people, because it was not only a matter of repopulating the biggest city of the Crown of Aragón, but also of all the Kingdom of Majorca. Well, there is not any architectural vestige where there should be some. There is not any vestige of the Catalan Romanesque, which was in its highest splendour in those times (11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th centuries), neither are there any vestiges of “masías”, the typical Catalan farmhouses, all the rural buildings adopting the style of each island. So we have the Majorcan farmhouses of a Roman- Andalucian style of triple hollow, to which we may reckon an antiquity of more than 2000 years.(1) The same antiquity may be established for the farmhouses of Minorca and Ibiza, the latter with its Middle-East type of constructions, clearly differenciated fron those of Majorca and Minorca. And we see that the Majorcan farmhouse has a rectangulas ground floor, its roof sloping towards the façade, or to the back of the house in older constructions. In more modern times, the buildings have a saddleroof sloping to the front and to the back of the house. The Catalan “masía” has a square ground floor with a saddle roof sloping to either side of the façade, which results in a different plan of the house, different from that of the Majorcan house. And we must bear in mind that the idea of people´s houses (in this case, of the Catalans who supposedly repopulated the islands) as some type of vital space in which families lived, a place of gathering that in the Middle Ages was a world in itself, a world of traditions, customs and cycles that were compulsory for their dwellers. And, from what we can see, there is no trace of that idea, of that house, as a Catalan sign of identity whereas it would be only too logical (as it is the case of any repopulated spot in the world) that the Majorcan landscape were covered with constructions of the Catalan type. And this simple fact leads us to the drastic conclusion that there was no Catalan repopulation in the Kingdom of Majorca after the year 1229. To that fact we must add the evidence that once the plundering had been accomplished, most members of the expeditionary force returned to their places of origin with their booty, and James the 1st himself avowed in his “Chronicle” that so few were the men who remained that they did not suffice to form the body of his personal guard, for which reason he recruited more people in Aragon. Under those circumstances it is a logical consequence that the repopulation would have proved rather difficult. If we add that, according to the “Llibre del Repartiment”, after the assault, a 75 % of the houses in Palma (2) were still occupied by their Majorcan owners, we may conclude that there was not any kind of repopulation with Catalans. (1 y 2, La casa popular Mallorquina. Carlos García-Delgado. 1996).

And since the cultural heritage of a people does not only consist of its idea of a dwelling, but of many other aspects of life, let us accept for a moment that the hypothetical repopulation of Majorca by Catalans had taken place. And that when they trod on Majorcan land they decided to occupy the abandoned dwelings; that they liked those so much that they did not modify them at all, keeping the distribution of the rooms; ando so much did they like those houses that when in need of more, they copied the Majorcan pattern instead of building Catalan farmhouses and, in doing so, denying their identity. And why not?! Let us accept it!

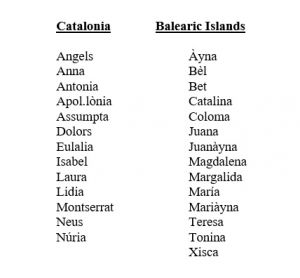

However, and even accepting that the cultural heritage of a people is not only its architecture, let us mention other signs of identity that the new settlers should have brought. And let us mention the very ultimate feature in a family: the real proof of somebody´s identity until the first half of the last century, the role of the identity of a differentiated people, as individuals who belong to a specific ethnic group. This aspect is precisely the proper name given to each one of us, to all the people in the Universe; which name is given to us by our parents or Godparents when we are born, a name, with the odd exception, for all our lives. A name that tell the others of our identity. For example, when someone tells us that his name is Klaus, it is to tell us that his identity is German; if the name is McGiver, we understand that the identity is Scottish; if François, French; if Enric, Catalan; if Iñaki, Basc; if Tomeu, Balearic, etc. Let us, from this point of reference, investigate whether there was, or was not a Catalan invasion, through a thorough study of the inhabitants´ (of the Balearic Islands) names, who should, in theory, be the descendants of those Catalans who hipothetically repopulated our Majorcan Kingdom.

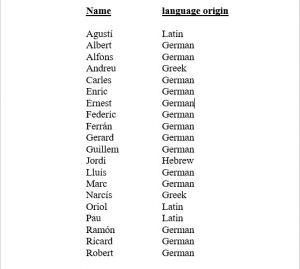

Let us first see some Catalan traditional proper names and their origin.

We see that a 70% of typical Catalan male names are of German origin; being the rest, a 20% of Latin origin; a 10% of Greek origin, and only a 5% of Hebrew origin.

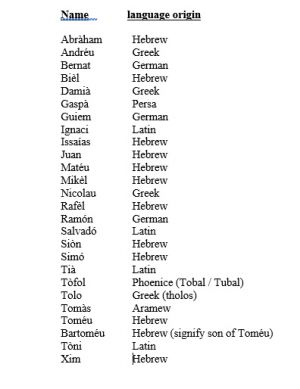

And now the males´ names in the Balearic Islands.

The variety of origins of the Balearic males´ names, is remarkable though not strange if we take into account the cosmopolitan character of the Archipelago; their sources being naturally and purely Mediterranean: Phoenician, Hebrew, Greek, Roman... with a predominance of those of Hebrew origin (Israeli) 48%, the rest being a 14% of Greek origin, 14% of Latin origin, and another 14% of varied origins.

From the aforesaid we may conclude that there was no Catalan repopulation of the Balearic Islands. Because the names of their inhabitants are not of a German origin, which is the case of Catalonia; and which should be the case of the Balearic inhabitants, had they been their descendants.

And now, some typical feminine names.

Notwithstanding the aforesaid, let us try and imagine ourselves in the Middle Age, in the midst of a rural and totally illiterate society, under the strict control of a progressively dominant and intransigent Christian religion, with an overwhelming number of prejudices, superstitions and traditions (that lasted until the end of the XlXth century), who controlled people´s lives with Swiss clockwork precision.Which means that if tradition told the parents to give their brood their grandparents´ names, they did as they were expected to; because if they did not act accordingly, they had to bear the permanent reproval of their folk and the scorn of their own family for having broken their rules. And those same rules applied to the customs in the agricultural and cattle trade, the locomotives of feudal economy.

Given our previous information, we may wonder: is it possible that as soon as they set foot on Majorcan land, those hipothetical Catalan settlers gave up their German names due to a sudden transformation that made them renounce their traditions and their Christian religion? Would anyone believe that they disowned their Christian religion of old christians and fervourously embraced the Jewish religion with such fanaticism that they gave their children Hebrew names in the stead of their traditional Christian-Germanic names? ...We sincerely believe that it was not so. And we affirm categorically and unequivocally, that the Kingdom of Majorca was never repopulated by Catalans.

Romance linguistic landmarks previous to Jaime the First.

Part of the toponymy in the Balearic language dates back to the times previous to the Reconquest, with toponyms that have survived until our times, linguistic milestones that prove the existence of the Balearic language before the Reconquest, such as the insults: “fava” /'fɑvɵ/ “favòta” /fɵ'vɒtɵ/ y “cap de fava” /cɑp dɵ 'fɑvɵ/, meaning foolish or silly, Neanderthaloid or Troglodyte, and the expression “¡me cagondéna!”, /mɵ 'kagon'denɵ/ that is the contraction of the phrase:“I shit on Denia!”. Which expression was used among the Majorcan people since the invasion of Majorca by the “Almoravides” (Moabites, in old Sp) of Denia in 1015, two hundred and forty years before the Reconquest.

This is why, with solid arguments supported by historical facts, we may here come to the end of our exposition by stating that the Balearic language and the Catalan language, with common roots though without a common sustratum, have followed a different evolutionary process in their own environement and through the use made by the community of speakers, independent from each other, because each community see and organize their surrounding world according to the language they speak; notwithstanding that the two languages share quite a few words and their meanings.

However, it is interesting to observe that in all the Spanish language books, when they refer to the pre-Roman languages and to the languages that issued from the Latin (Neolatin (The origin of the Neolatin languages, Carlo Tagliavini) and Romanic), never, never ...is anything said of the language that was spoken in the Balearic Islands.It is as if these Islands had been always uninhabited until the Conquest. Yet they mention the existence of the Tartessian, spoken in Portugal and in the Western half of Andalusia. They also mention the Iberian, spoken in the Eastern half of Andalusia, the eastern coast of Spain, the Ebro river valley, the present-day Catalonia, and areas of southern France. The Basc is also mentioned, spoken in the Basc Country and in an area of south-western France. They mention the Celtiberian, spoken in Burgos, Logroño, Navarra, Soria, Guadalajara, western Zaragoza and Teruel.

But nothing is said about The Balearic Islands. Nothing, as if the Archipelago did not exist. Notwithstanding that the Islands were already a commercial power in the Phoenician era, long before the foundation of Cadiz. Because the Balearic Islands were precisely the bridge that allowed the Phoenicians to settle on the eastern coast of Spain and in the Strait of Gibraltar. Consequently, and to say the least, the Phoenician language must have been spoken in the Balearic Islands in that era, when also the Hebrew of the time of the Exodus came to the Archipelago with linguistic milestones such as “crespell /krɵs'peļ/, robiol /ŗobi'ɒl/, magalluf /mɵgɵ'ļuf/, moixí /moi'ʃi/” etc. Later on there were Greek settlements, whose people also left their linguistic landmarks such as “atapíns /ɵtɵ'pins/, rohélla /ŗo'ellɵ/, estada /ɵs'tɑdɵ/, pantalèu /pɵntɵ'lεu/, bastaxos /bɵs'tɑʃos/, artà /ɵr'tɑ/,” etc. And much later came the Vulgar Latin, along with the Iberian language with the Iberian families brought by Quinto Cecilio from the Peninsula to populate the centre of Majorca; from them remain the iberian words (in the euskera or Basc language), (Scientific Magazine, Mysteries of Archeology. Year the 1st, number 3, 1996. Jorge Alonso): “zerra, aloguer, ostatu, galant, pitxar, jake, garau, gari” etc.; in Majorcan, “sèrra /'sεŗɵ/, llogué /ļo'ge/, hostal /os'tɑl/, galant /gɵ'lɑnt/, pitxé /pi't͡ʃe/, jac /ʒɑk/, Garau /gɵr'rɑw/, Garí /gɵ'ri/,” last two words have become surnames. But the Balearic Islands was already a nation well known in the civilized world of those times, with its own language, with which its inhabitants were able to communicate with most of the Mediterranean cultures, since the Mare Nostrum was dotted with Phoenician colonies, and in those settlements commercial trade was enriched with language interchange.

When the Balearic Islands became part of the Roman world and subsequently reached the category of a Roman Province, their language got richer and evolved by itself until the first Arab invasion in 799 that forced their inhabitants to ask Alexander the Great for help, and he sent an armada that defeated the Sarracen navy; (General History of the Kingdom of Mallorca. Volume ll, pages 701 to 705. D. Juan Dameto, 1841) and so grateful were the natives that they swore fidelity to Alexander as their sovereign, the result of which was an important settlement of Provençal-Occitanian people. And thence the abundance of Provençal-Occitanian expressions in the Balearic Language, which expressions were in no way acquired through the conquest of James the 1st, nor from any Catalan insular factor; being a peculiarity of the Balearic language its feature of having preserved its purity and richness due to the insular factor. All that happened 430 years before the Reconquest and 2 years before Alexander the Great took Barcelona from the Arabs, Subsequently, in 814 and shortly before his death, he named his grandson Bernardo, Pipino´s son, king of Italy and of the Balearic Islands (Idem, volume ll, pages 701 to 705. D. Juan Dameto, 1841). (Thence the abundance of the name Bernàt in our Islands). Later on, in 832, the Saracens tried another invasion but they were defeated by the Balearic-Occitanian. It was the year 856, (57 years after the arrival and settling of the Provençal-Occitanian), when Bona, the Northafrican king, succeded in conquering Palma. Many Majorcan aristocrats (idem, volume ll, pages 566 and 763. D. Juan Dameto, 1841) and plebeians fled to the coasts of the Ampurdan in the northeast of Catalonia, because the shores of Barcelona did not provide safe shelter for the ships due to their consisting of sandy strands, besides being too close to the areas occupied by the Arabs. A historical fact that proves why the Balearic articles “sa, es /sø, øs/”, are used in that region of Catalonia. And when in 1228 James the 1st distributed the kingdom of Majorca, in case it was conquered by others, attributing himself the right of ownership on all the castles of Majorca, D. Nuño Sanz, count of the Roussillon told him that the castle of Montueri was his, because it belonged of old to his family, which fact was stated in a document on the 10th of January 1228, and ratified by another document dated September the 5th 1229. And a question rises here: how is it possible that the castle belonged to his family of old, being it the first time that the conquest of Majorca had taken place? The answer will be found in the facts we are stating though not in the fact that the Balearic Islands had been repopulated with settlers from the Ampurdan, being the use of articles like “es” and “sa” a natural consequence of the Catalans settling in Majorca, as it is taught at the schools and written in the students´ textbooks. It so happened that in 859 the Balearic Islands were invaded by the Normans, and the natives enriched their ancient language with words of German origin such as, to give an example of the remaining expressions, “Frau” /'frɑw/ (Frawi), as a surname which meaning is Mrs., and the words: “trescà /trɵs'kɑ/, gana /'gɑnɵ/ etc. The Arabs subsequently reconquered the Balearic Islands and so did, later, the Christians of Jaime the 1st.

Regarding History, we could stop at this stage of our study, because the word is linked to the person´s history as an individual who is part of a group called nation, kingdom; or, simply, people. And from our historical approach, we have proved that there is neither document nor fact on which we might found the theory of any sort of repopulation in the Balearic Islands after 1229.

The Spanish, the Balearic and the Catalan languages. A comparative philological study.

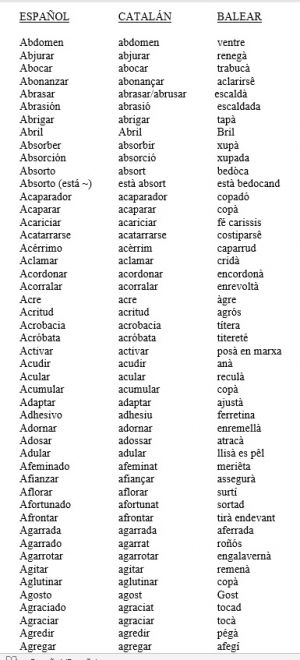

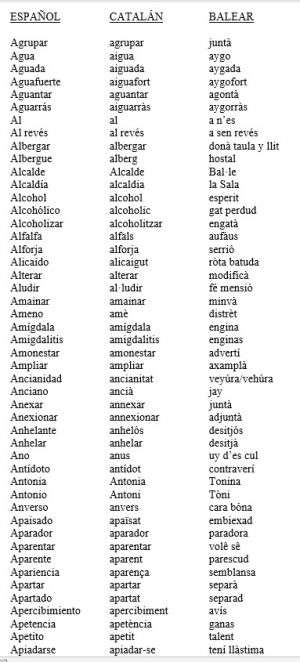

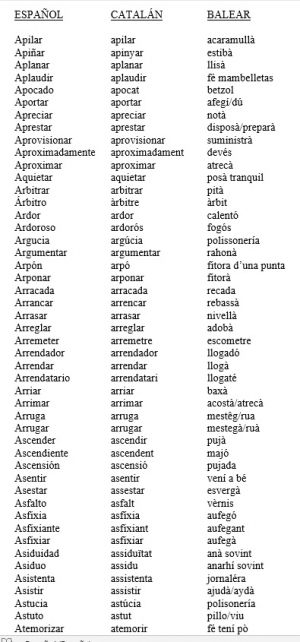

Notwithstanding the aforesaid, let us tread the philological field and give a sample of comparison between the Spanish, the Balearic, and the Catalan languages. It must be understood that the given Balearic orthography was approved in the “1st Congress of Balearic Philology” in 1992-1993, which little differs from that of the last Majorcan Grammar of 1872. It was the orthography used by he Majorquinist intellectuals at the end of the XlXth century and at the beginning of the XXth century; to the names of those intellectuals mentioned above, we shall add that of D. Pedro Alcántara Peña.

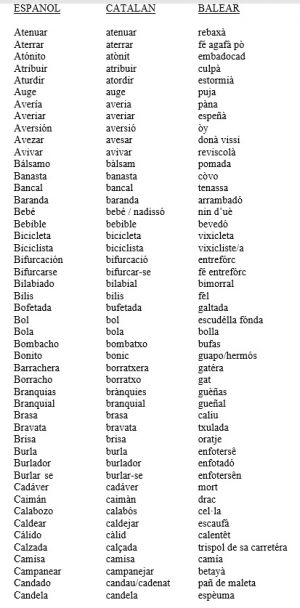

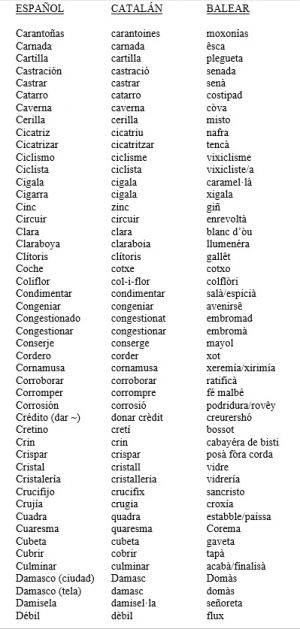

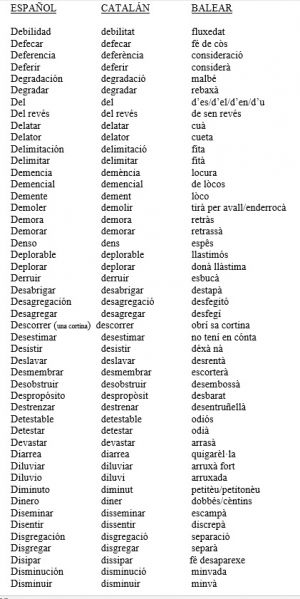

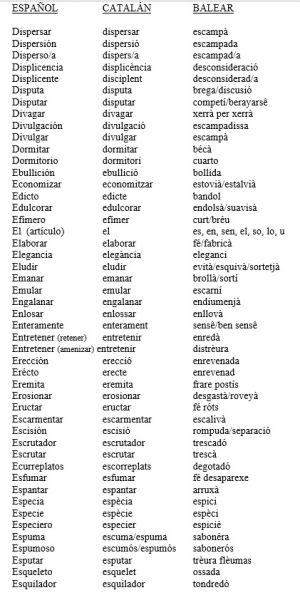

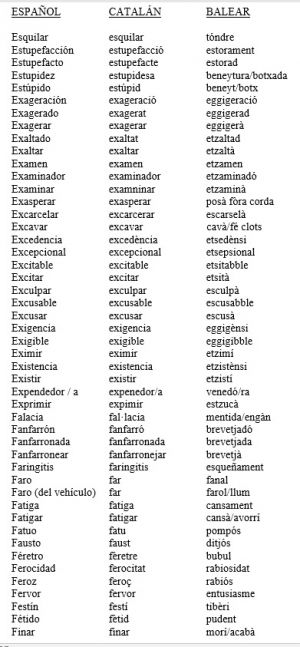

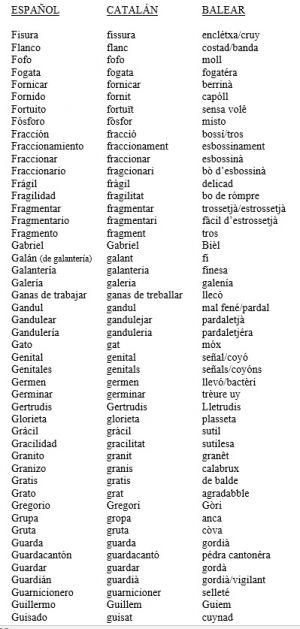

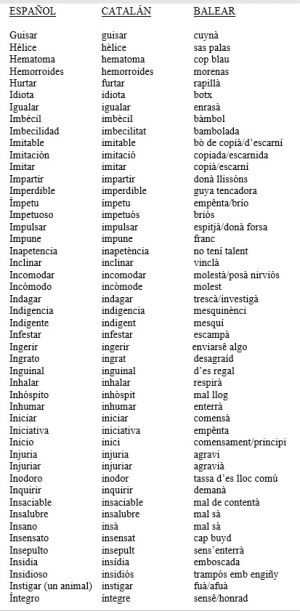

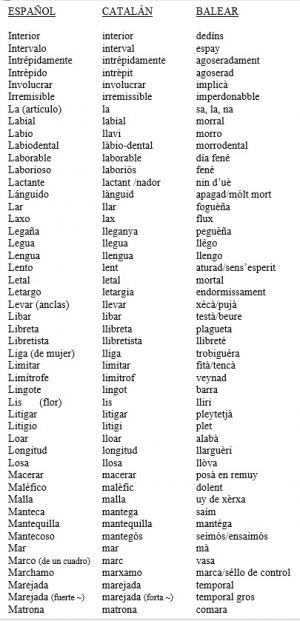

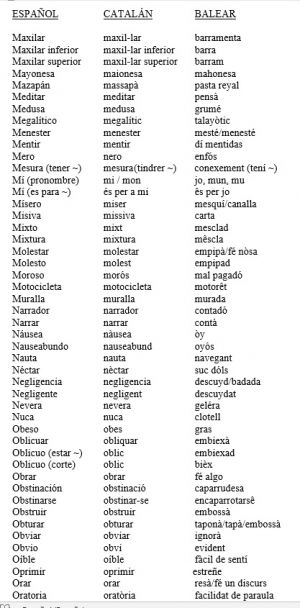

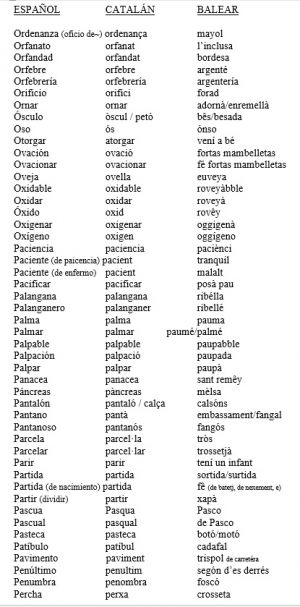

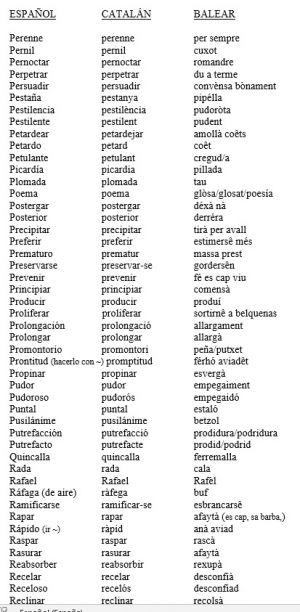

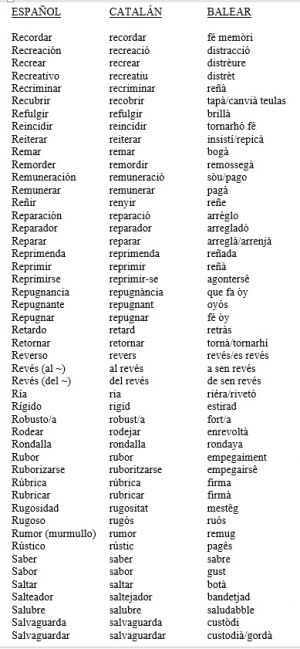

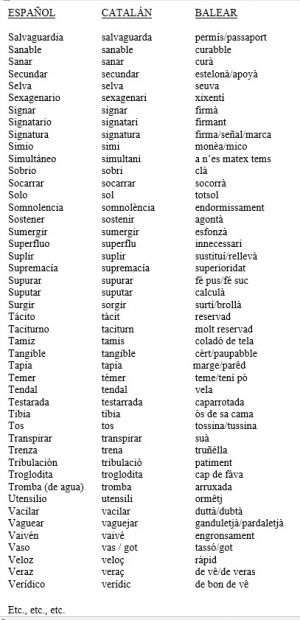

List of expressions with the same meaning.

We have taken the list of Spanish and Catalan words from the:

“Diccionari manual VOX. Castellano-Catalán/Català-Castellà. 1997.”

With a first prologue in Spanish by the Illustrious D. Camilo José Cela, and a second prologue by the Illustrious D. Antoni María Badía i Margarit (President of the Department of Philology at the “Institut d´Estudis Catalans”, the highest Catalan linguistic institution).

(We have written in bold type the words that are equal in Spanish and Catalan, but for the accents and hyphens).

After seeing that list, which do you think is a dialect of which? Couldn´t we openly assume that the Catalan is a dialect of the Spanish, and the Balearic language is undoubtedly a language different from the Spanish and the Catalan?

However, to affirm that one language is a dialect of another language, it does not suffice that the two tongues in question have several thousand words in common, words that are homonymous, orthographically equal and with the same meaning, neither does it suffice that several thousand words of one language be included in the dictionary of the other language (it happened with the Balearic language that, in a pompous ceremony at the presentation of the new Catalan language dictionary, in November 1995, D. Juan Miralles, director of the department of Catalan philology at the University of the Balearic Islands, boasted that thanks to his department, the new dictionary of the Catalan language included 700 Balearic words that would from that moment increase the Catalan lexis). What marks the limits between languages is their linguistic structure. And the structures of the Spanish, the Balearic, and the Catalan, are different from each other, as we shall see.

From the Vulgar Latin originate, first the Neolatin languages (Origin of Neolatin Languages. Carlo Tagliavini) and then the Romance Languages, through the Latin merging with the local languages. This fact supports the philological axiom that:

IT IS THE PEOPLE, NOT THE LINGUISTS, WHO MAKE THE LANGUAGES.

With the excepction, of course, of synthetic languages; this is to say, languages produced in linguistic laboratories.

So taking into account that the meaningful values of each word or significance are established by the people who speak the language, who also establish the changes and broader uses in the semantic field and their final acceptance or refusal by the community, let us have a look at the linguistic structures of the Spanish, Balearic and Catalan languages.

LINGUISTIC STRUCTURE

It is known that all languages are based on pillars which are common in their denomination although different in their contents; they are, at the same time, systems of signs in which we can detect the difference between languages when compared. All that system is called linguistic structure.

Those pillars are:

Phonologic, morphosyntactic and semantic.

It is said and it is established as a principle that just one difference between those systems is enough to accept them as different languages.

Yet we shall forthwith prove that there is more than one difference between the Balearic and the Catalan languages.

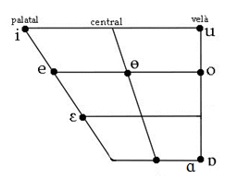

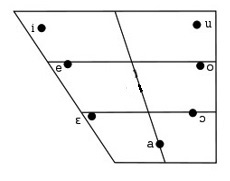

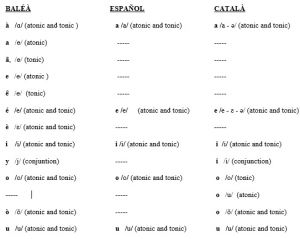

Phonologic system.

We shall start from the beginning, with the phonologic system of the languages in question, in order to clarify which is a dialect of which, or if they are in fact three languages with the same roots though different from each other.

When the letter “i” forms a diphthong with a preceding vowel and consequently loses part of its natural sound, “i” is replaced by the letter “y”.

Examples: cuy /'kuj/ (take);

fuya /'fujɵ/ (leaf);

vermêy /vɵr'mɵj/ (red);

beya /'bɵjɵ/ (bee).

Balearic syllabic subsystem of double consonants.

(they are separable).

The letter b is doubled in all the words ending –bla, -ble, -bli, -blo:

amóbblà (a-mob-blà) /ɵ-mob-'bla/

pobble (pob-ble) /'pŏb-blɵ/

púbblic (púb-blic) /'pub-blik/

fibbló (fib-bló) /fib-'blo/

The letter c is doubled in:

accident (ac-ci-dént) /ɵ-t͡si-'dent/ and its derivative words.

acció (ac-ció) /ɵ-t͡si'o/ and its derivative words.

The letter g is doubled in:

lliggí / lleggí (llig-gí / lleg-gí) /ļig-'ží/, /ļɵg-'ží/ and its derivative words.

correggí (co-rreg-gí) /ko-ŗɵg-'ži/ and its derivative words.

The letter l is doubled in:

mòl·lo (mòl-lo) /'mŏllo/

mêl·la (mêl-la) /'mɵllɵ/

Bal·le (Bal-le) /'Ballɵ/

amel·ló (a-mel-ló) /ɵ-mɵl'lo/

The letter m is doubled in:

semmana (sem-ma-na) /sɵm-'ma-nɵ/ and its derivative words.

emmagrí (em-ma-grí) /ɵm-mɵ-'gri/ and its derivative words.

The letter t is doubled in:

sutjettà (su-tjet-tà) /su-'žɵt-'ta/ and its derivate words.

dissatte (di-ssat-te) /di-'sat-tɵ/

adjettiu (ad-jet-tiu) /ɵd-žɵt-'tiu/ etc.

The letter n is doubled in:

ànnera (àn-ne-ra) /'an-nɵrɵ/ and its derivate words.

ennobblí (en-nob-blí) /ɵn-nob-'bli/ and its derivate words.

ennigulà (en-ni-gu-là) /ɵn-ni-gu-'la/ and its derivative words.

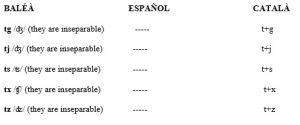

Balearic syllabic system of consonant groups.

(they are inseparable)

tx = [ʧ] tz = [ʣ] tj = [ʤ]

tg = [ʤ] ts = [ʦ] cc = [ʦ]

cotxo ['koʧo] co-txo = car

dotze ['doʣɵ] do-tze = twelve

corretja [ko'rɵʤɵ] co-rre-tja = strap

metge ['meʤɵ] me-tge = médico

catsa ['kɑʦɵ] ca-tsa = box

dicció [diʦi'o] di-cció = diction

The Catalan syllabic system of consonant groups.

(they are separable)

tx = t + x > /t + ĉ/; cotxe (car) cot-xe /'kot-ĉə/

tz = t + z > /t + z/; dotze (twelve) dot-ze /'dot-zə/

tj = t + j > /t + ž/; corretja (strap) cor-ret-ja /kor-'ret-žə/

tg = t + g > /t + ž/; metge (doctor) met-ge /'met-žə/

ts = t + s > /t + s/; potser (maybe) pot-ser /put-'sε/

The Balearic accentuation.

The Balearic language has three types of accentuation

Orthographic accent: oxytone, paroxytone and proparoxytone. With three written accents: /´/ acute, /`/ grave/, and /^/ double, (formerly called circunflex accent).

Phonetic accent: It indicates the different pronunciations of the vowels, regardless of their position in the word. It has two written forms: /´/ acute, and /`/ grave.

a /ɵ/: camía /kɵ'miɵ/ (shirt).

à /a/: cassa /'kasɵ/ (house); cassà /kɵ'sa/ (hunt); caminà /kɵmi'na/ (walk).

e /ø/: deu /'dɵu/ (must) ; necessidat /nɵsɵsi'dat/ (necessity).

é /e/: Déu /'deu/ (god) ; péssa /'pesɵ/ (piece).

è /ε/: dèu /'dεu/ (ten) ; ubèrt /u'bεrt/ (open).

o /o/: colóm /ko'lom/ (pigeon); comodí /komo'di/ (nigtstand)

ò /ŏ/: ò /ŏ/ (gold) ; còssi /'kŏsi/ (clay pot).

The diacritic accent

Has three written form, /´/, /`/, /^/, and the latter it is used on the third person singular “essê /ɵ'sɵ/”, (be) to distinguish it from the singular masculine article “es /ɵs/” (the).

Example: ês es cavall /'ɵs ɵs cɵ'vaļ/ (It is the horse).

On the noun “rês” to distinguish it from the adverb of quantity “res” (nothing.

Examples: no vuy sabre rês /no vuj 'sɵbrɵ rɵs/ (I don’t want to hnow nothing); res més /rɵs mes/ (nothing more); no heyà res /no ɵj'a rɵs/ (there is nothing).

The closed accent is used on the third person singular of the verb to be “éts” to differentiate the masculine article plural “ets”.

Examples: éts es derré /ets ɵs dɵ'ŗe/ (are the last); ets ases /ɵts 'azɵs/ (donkeys).

The open accent is used for example on the word “ò” (gold) to differentiate it from the letter “o” conjunctiva.

Examples: es cotxo d’ò /ɵs 'kočo dŏ/ (the gold car); axò o allò /ɵ'ʃŏ ŏ ɵ'ļŏ/ (this or that).

Important

When there are two or more phonetic accents on the same word, the stress is always on the last accentuated syllable.

Examples: generalment /žɵnɵ'ral'ment/ (generally); téòric /te'ŏrik/ (theoretical); baléà /bɵle'a/ (Balearic); periòdicament /pɵriŏdicɵ'ment/ (periodically)

The Catalan accentuation.

The Catalan language has two types of accentuation, the orthographic accent: Oxytone, paroxytone and proparoxytone, with two written forms: /´/ acute and /`/ grave.

And the diacritic accent, are two /´/ closed accent and /`/ open accent, to distinguish words with the same spelling but with a different meaning.

Example: nét – net (grandchild – clean); pèl – pel (hair – for him).

Morphosyntactic System.

Independent morphemes and dependent morphemes

The Independent morphemes ar:

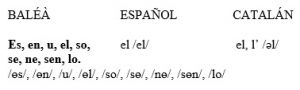

Articles.

Singular masculine articles.

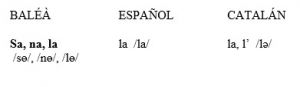

Singular femenine article.

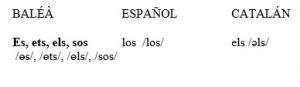

Plural masculine article.

Plural feminine article.

Balearic use of articles.

The articles “u, el /u/, /ɵl/” (the) are both used when we want to magnify the name they precede, or when we want to give it an ironic intention.

Examples: U Papa /u 'papɵ/ (the Pope); el Réy /ɵl rej/ (the King); el señó Ministre /ɵl sɵ'ņo mi'nistrɵ/ (the Sir Minister); el Mallorca F.C. /ɵl mɵ'ļŏrcɵ/ (the Majorca Football Club).

¡Miratêl a n’el réy...! /mirɵ'tɵl ɵ nɵl rej/ (look at the king..! referring to someone who wants to get everything done).

The article “es” /ɵs/ (the) is the singular masculine Balearic article par excellence. It is used before all masculine words beginning in consonant.

Examples: es cavàll /ɵs kɵ'vall/ (the horse); es cotxo /ɵs 'koĉo/ (the car); es pitxé /ɵs pi'ĉe/ (the jar of water); es réy de ca nostra /ɵs rej dɵ ka 'nŏstrɵ/ (the king four house).

The article “se” /sɵ/ (the) is used only with masculine words beginning in a vowel, losing (the article) its vowel due to the liaison.

Examples: s’Impèri /sim'pεri/ (the Empire); s’ase /'sazɵ/ (the ass); s’aygo /'sajgo/ (the water).

The article “so” /so/ (the) always follows the preposition “emb” /ømb/ (with).

Examples: emb so cavall /ɵmb so cɵ'vaļ / (with the horse); emb so guinavet /ɵmb so ginø'vɵt / (with the knife).

The article “ne” /nɵ/ (the) is used before nicknames beginning in vowel, especially when there is a friendly or familiar link between the speaker and the person addressed. It also loses its vowel due to the liaison.

Examples: n’oreyòtas /norɵj'ŏtɵs/ (big ears); n’Andréu /nɵn'dreu/ (the Andrew).

The article “en” /ɵn/ (the) is used in the same way as “ne” for names beginning in consonant.

Examples: es llibre d’en Juan /ɵs 'ļibrɵ dɵn žu'an/ (John´s book), (when the preposition “de” is followed by the article “en”, it can be translated into Spanish by the preposition “de” (of),= El libro de Juan); en rós /ɵn ros/ (the blond, used either as a nickname or referring to a male animal); en mux ês un bon al·lot /ɵn muò ɵs un bŏn ɵl'lŏt/ (the “mush” (nickname without possible translation) is a good boy).

The article “lo” /lo/ (the) is used in the same way as the articles “es” and “se”, or even instead of them.

Examples: lo cotxo /lo 'koĉo/ the car; lo sendemà /lo sendɵmá / (the next morning); tireu a l’yare / ti'rɵu ɵ 'lajrɵ / (throw into the air); londemà /londɵ'ma / (the following day).

The article “sen” /sɵn/ (the) is used only between the prepositions “to” and “of”, and with the expressions “back side”, “right”, and “front side”.

Examples: “back to front”; “upside down”; “inside out”, “front side”, “upright”, “the outside”.

a sen revés /ɵ sɵn rɵ'ves/ (upside down); a sen dret /ɵ sɵn drɵt/ (the rigt); de sen revés /dɵ sɵn rɵ'ves/ (inside out); de sen dret /dɵ sɵn drɵt/ (the rigt); per sen dret /pɵr sɵn drɵt/ (for about); devés sen dret /dɵ'ves sɵn drɵt/ (about); per sen endret /pɵr sɵn ɵn'drɵt/ (in front of); a sen endret /ɵ sɵn ɵndrɵt/ (in front of).

The article “la” (feminine “the”) is used when we want to emphasize the noun that follows, when we want to give the expression an ironic quality, and also with the first hour of the day and its fractions.

Examples: la ma /lɵ ma/ (the sea), la Vèrge /lɵ 'vεržɵ/ (the Virgin), ¡mira la bélla dòna!... /'mirɵ lɵ 'beļɵ 'dŏnɵ/ (Look at the beautiful woman!...); la una /lɵ 'unɵ/ (one o´clock), la una y dèu /lø 'unɵ i 'dεu/ (one ten).

The article “sa” (feminine “the”) is the Balearic singular femenine article par excellence, used before all femenine nouns beginning either with a vowel or a consonant.

Examples: sa soméra /sɵ so'merɵ/ (the she-donkey); sa ma /sɵ ma/ (the hand); sa verja /sø 'vεržɵ/ (the virgin); s’igglesi /sig'glɵzi/ (the church).

The article “na” (feminine “the”) is used before nicknames, domestic animals´names and Christian names in a familiar or friendly sense.

Examples: na blanca /nɵ 'blankɵ/ (the white one, referring to a female animal); na Tonina /nɵ to'ninɵ/ (the Antonia); na pellusca /nɵ pɵ'ļuskɵ/ (the pellusca, soubriquet).

The Dependent morphemes.

Formation of the Balearic plural (some examples).

As a general rule, the Balearic plural is formed by adding an -s to the singular.

The plural femenine is always formed by adding the termination -as to the noun.

Examples:

negre /'nɵgrɵ/ (black msc.) > negres /'nɵgrɵs/;

negra /'nɵgrɵ/ (black fm.) > negras /'nɵgrɵs/;

cavall /kɵ'vaļ/ (horse) > cavalls /kɵ'vaļs/;

casa /'kazɵ/ (house) > casas /'kazɵs/;

bosc /'bŏsk/ (forest) > boscs /bŏsks/.

Words ending in -rt, -nt, -lt, lose their t in their plural form.

Examples: mort /mŏrt/ (late) > mors /mŏrs/ (lates)

abundant /ɵbun'dant/ (plenty) > abundans /ɵbun'dans/ (plentys)

mòlt /mŏlt/ (milled) > mìols /mŏls/ (milleds)

molt /molt/ (much) > mols /mols/. (very much)

Formation of the Catalan plural (some examples).

In Catalan, the plural is generally formed by adding an -s to the singular. Exception: if the singular femenine ends in atonic “-a”, the “a” becomes “-es”.

Examples: casa /'kazə/ (house) > cases /'kazəs/;

negra /'nεgrə/ (black fm.) > negres /'nεgrəs/;

negre /'nεgrə/ (black msc.) > negres /'nεgrəs/.

The plural of words ending in -ç, -s, -sc, -st, -xt, -x, -tx, is formed by adding –os.

Examples: bosc /bɔsk/ (forest) > boscos /'bɔskos/;

gest /žest/ (gesture) > gestos /'žestos/;

peix /pe∫/ (fish) > peixos /'pe∫os/;

text /tεkst/ (text) > textos /'tεkstos/.

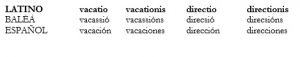

The verbals conjugations

Let us now see the verbal endings and conjugations, of which the Balearic has four types, in contrast with the three conjugations of the Spanish and the Catalan:

Verbal endings

In the Romanic Philology treatise entitled “Lexicon der Romanistischen linguistic”, 1991, page 139, we read as follows: “...in the monosyllabics, the Romanic final “r” disappears in Balearic, stressing that disappearance. In infinitive nouns, the final Romanic “ere” appears when an enclitic pronoun is accompanying the verb.”

Yet, that Romanic final “r” is used in Lemousin, Spanish, Galician, Valencian and Catalan.

The begowned National-Catalanists defend the theory that the infinitives must be written with the final Romance “r” even though it be not pronounced, because the future tense cannot be formed without it.

But when the reasons given to prove a theory are based on false grounds, that theory crumbles itself to pieces, as it is the case.

The fact is that the evolution of the Latin language in the provinces produced what was later called the Romance languages. There was, however, a previous step, the first step to the way out of the mother tongue craddle, during which the Neolatin was formed. But the majority (of scholars), (maybe due to the very few languages that survived), avoid mentioning the Neolatin, or they mention it just as a synonym of the Romance languages. Yet the fact is that the Neolatin survived in some provinces (origin of the Neolatin languages, Carlo Tagliavini), or the Pre-Romance, which is but a transition from the Common Latin to the Romance, widely spread through the works of the Christian priests and monks. The provinces that have kept the original form of the Neolatin endings are: La Provence, the Balearic Islands and Romania.

And let us now see a sample of the infinitive in the three languages:

ROMANIAN BALEARIC PROVENÇAL Abandona Abandonà Abandouna ------------ Abeurà Abeoura Abdica Abdicà ------------- Abjura Abjurà ------------- ----------- Agradà Agrada Abolí Abolí -------------- ------------ Amagà Amaga Abona Abonà -------------- ------------- Alenà Arena Abrevia Abrevià -------------- ------------- Rapà Arrapa Abuza Abusà -------------- ------------- Badà Bada Aclama Aclamà -------------- ------------- Badayà Badaya Aclimatiza Climatisà -------------- ------------- Barbetjà Barbejha Acupla Acoplà -------------- ------------- Bécà Beca Activa Activà -------------- ------------- Beure Beoure Acumula Acumulà --------------- -------------- Blanquetjà Blanquejha, etc.etc.etc.

The Great Eciclopaedia Rialp, p.185, says thus of the Balearic language:

“...Among all Romance languages, the Balearic has preserved the most archaic tendency”. A good proof is that the Balearic has kept the diphtong “ei”. Here follows an example in a popular poem dedicated to the authoress of the Normalization Law of the Catalan in the Balearic Islands:

No duguis tant’eleganci, que sabêm d’hon prosedêis, (come from) y de tant que presumêis, (show off) es téu nom fa oló de ranci. Vas carregada d’ignoranci, fins a sa rèl de’s cabêys, escoltand cuatre benêys, que t’han donada importanci.

And how it is possible, in Provençal, to form the future tenses from the infinitives without the final Romance “r”, by simply, because adapting orthography to phonetics.

verbe ave in Provençal. (verb to have) (in Baléà is: havê /ɵ'vɵ/).

Pres. Ind.: -ai, -as, -a, -avem, -avès, -an.

Perf. future: aourai, aouras, aoura, aourem, aourès, aouran.

Imperf. future: aouries, aouriès, aouria, aouriem, aouriou, aouríen.

verbe castiga in Provençal. (in Baléà is: castigà /kɵsti'gɑ/).

Futuro Perf.: castigarai, castigaras, castigara, castigarem, castigares, castigaran.

Futuro Perf.: castigaries, castigariès, castigaria, castigariem, castigariou, castigaríen.

So we have proved the falsehood of the theory that the formation of the future tense is not possible lest the infinitives end in a Romance “r”; and the theory that states the impossibility of suffixing nouns ending in tonic “-e” instead of Romance “r”, as in the cases of “ferré, fusté, jardiné”, etc. (blacksmith, carpenter, gardener).

It is our opinion that those who defend that theory must have a really acute mind, since, according to the same principle, it could be stated that nouns ending in tonic –a, -e or –u, such as “capità, ple, comú”, (captain, full, common), whose femenines are “capitana, plena, comuna”, should be written “capitàn, plen, común” in their feminine form. However, it is clear that the final “n” should not be pronounced, because Ferrer´s Romance final “r” must be written but not pronounced. And it is also clear that this rule is acceptable in Catalan but not in Balearic. Because the written Balearic reflects exactly the spoken language of the Balearic people.

On the other hand, if we accept the loss of the final Romance “-n”, MANU = MÀ, and its reappearance in the plural, “màns”, we must also accept the loss of the Romance “-r” in the infinitives although it reappears when linked to an enclitic pronoun:

Dú > durhó, durhí. Menjà > menjarhó, menjarhí.

That is why in Balearic the syllable “-ra” is added to form the feminine of nouns ending in tonic “-e”: ferré > ferréra /fɵ'ŗerɵ/, fusté > fustéra /fus'terɵ/, jardiné > jardinéra /žɵrdi'nerɵ/.

In Balearic, this role can be seen in the surnames: Llabrés, Fornés, Arqués, Sitjàs, Ferrés, Arbonés, Argilés, etc., which are the plural of: llabré (hound), forné (baker), arqué (archer), sitjà (place of silos), ferré (blacksmith), argilé (potter), without the final Romance “r”.

Balearic tonic (strong) personal pronouns.

Singular : Jo /žŏ/, tú /tu/, éll /eļ/, élla /'eļɵ/, mí /mi/, sí /si/, emb jò /ɵmb žŏ/, vostê /vŏs'tɵ/.

Plural: noltros /'nŏltros/, noltras /'nŏltrɵs/, voltros /'vŏltros/, voltras /'vŏltrɵs/, vostês /vŏs'tɵs/, élls /eļs/, éllas /'eļɵs/, sí /si/.

Catalan strong personal pronouns

Singular: jo /žŏ, jŏ/, mi /mi/, amb mi /əmb mi/, tu /tu/, ell /ell/, ella /ella/, si /si/, vostè /βus'tε/.

Plural: nosaltres /nu'saltrəs/, vosaltres /βu'saltrəs/, vostès /βus'tεs/, ells /eļs/, elles /'eļəs/, si /si/, nos /nos/, vos /βos/, us /us/.

Balearic atonic (weak) personal pronouns.

Singular: me /mɵ/, em /ɵm/, te /tɵ/, et /ɵt/, el /ɵl/, la /lɵ/, li /li/, lo /lo/, se /sɵ/, es /ɵs/, en /ɵn/, ne /nɵ/, hi /i/, ho /o/, hey /ɵj/.

A neuter: ho /o/, eu /ɵu/.

Plural: mos /mos/, vos /vos/, els /ɵls/, elz /ɵlz/, elza /'ɵlzɵ/, euz /'ɵus/, euza /'ɵuzɵ/, las /lɵs/, lis /lis/, los /los/.

Catalan weak personal pronouns

Singular: em /əm/, ‘m, -me /mə/, m’ , et /ət/, t’ , -te /tə/, ‘t, el /əl/, ‘l, l’, -lo /lo/, la, -la /lə/, ho /u/, -ho /u/, li, -li /li/, es /əs/, s’ -es /əs/, s’, hi, -hi /i/, en /ən/, ‘n, n’, -ne /nə/.

Plural: ens /əns/, ‘ns, -nos /nos/, -vos /βos/, us, -us /us/, els /əls/, -los /los/, ‘ls, les /ləs/, -los /los/, -les /ləs/, els /əls/, es /əs/, s’, ‘s, -se /sə/

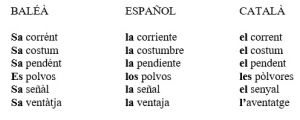

Different use of gender in balearic, espanich and catalan

Formation of compound nouns and expressions.

Pronominal expressions:

BALÉÀ ESPAÑOL CATALÀ

Informauvós informaros informau-vos-en

S’informin se informen informa-sin

Trèulamê sácamela treu-la’m

Escriulasmê escríbemelas escriu-me-les

The morphosyntactic differences are plainly evident.

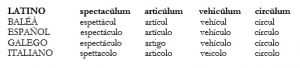

The family Iberian-Italian-Romance language.

As we can see in the table, the Iberian and Italian Romance languages (Balearic, Italian, Spanish, Galician and Portuguese), evolve by opening the pronunciation of the final unstressed u towards -o, thus losing the enclitic consonant.

The same occurs in the Latin endings -culum, where the disinencial combination -um, generally in Balearic Islands, is lost in its entirety (-cul). While in Spanish, Galician and Italian only the enclitic consonant is lost, and the unstressed vowel -u- declines in Spanish and Galician towards –o (-culo) with exceptions; while in Italian they are the two vowels -u-u that decline to -o- (-colo).

The same is true of the Latin endings -tio, -tionis.

More examples of linguistic affiliation:

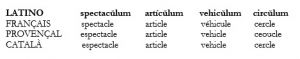

The family Iberian-Gallic-Romance language.

The same earlier Latin endings decline differently.

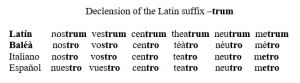

Declension of the Latin suffix -trum

As we can see, the Latin ending -trum declines towards -tre in all those Gallo-Romanesque languages.

Declension of the Latin suffix -culum

As we can see, the Latin ending -culum declines towards -cle in all those Gallo-Romanesque languages.

The same is true of the Latin endings -tio, -tionis.

Where the declension of the Latin ending -tio, -tionis is different from the Ibero-italo-Romance languages, declining towards -nce, -nces, -esse, -esses.

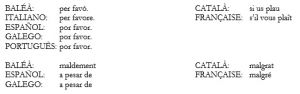

Semantics

We all know that if two or more people wish to communicate, they must speak or write and understand the same language. Otherwise it would be impossible for them to understand each other. This is to say, that any type of rational communication will prove impossible for a Spaniard and a foreign person if one of them does not know the language of the other one. However, mutual understanding may occur in spite of none of the speakers knowing each other´s language. It is the case of the Balearic and the Catalan people, who may understand each other without knowing each other´s language in depth. This circumstance is used by the Balearic national-catalanists, who conclude that “if I make myself understood when speaking to Catalan people in Majorcan and if I understand the Catalans perfectly, it is because the two languages are the same”. But at this point we must remind them that the Balearic people, and especially Majorcan people, have always had the ability of understanding not only the Catalans, but anybody else. Could it be that we still retain some Phoenician blood? The truth being, on the other hand, that it is very difficult for a Catalan to understand a Majorcan speaker; in fact it has always been the initiative of the Catalans to ask the majorcans to switch to Spanish in order to understand what they say!. With the exception of few cultivated people.

Here we must resort to the field of semantics: the meaning of the word, what the speaker wants the listener to understand. And here follow some examples:

Español : no ponga gasolina con el motor en marcha.

Baléà : no pòsi vénzina emb so motor en marxa.

Català : no feu gasolina amb el motor engegat.

In Catalan, this sentence does not have the meaning it has in Balearic, the Catalan meaning being “do not fill your petrol tank when the engine is running.” A Balearic speaker would misconstrue “do not make petrol if you have thrown the engine away”.

Because “feu” in Balearic means “do”, not “put”; and “engegar” in Balearic means “fire somebody”, “give the sack”.

Another example:

Español: tengo un regalo para tí.

Català : ting un regal per a tú.

Baléà : teng un regalo per tú.

The Catalan sentence would be given this meaning by a Balearic speaker: “I have a pubis for you”. Because “regal” does not have the same meaning in both languages, it being “pubis” in Balearic and “gift” in Catalan.

One more example:

Español: Papá se levanta a las ocho y a las nueve mamá. (Dad gets up at eight and Mom at nine.)

Català: El papa es lleva a les vuit y a les nou la mama. [al 'papa əs 'l̩eβa a ləs 'βujt i a ləs nŏw la 'mama]

Baléà: Es papà se xéca a las vuyt y a las nòu sa mamà.

The meaning of the sentence in Catalan for a Balearic speaker is: “The Pope gets out of the way at eight and performs a fellatio at ten”.

Because “el papa” means “the Pope” in Balearic; “es lleva” in Balearic means “he gets out of the way”, and “la mama”, “la” being direct object pronoun, means “(he) sucks it”.

The existence of different pronouns, different verbs and different articles is easily noticeable. Thence the misinterpretation of the Catalan by the Balearic speaker. (Nowadays, after eighteen years of Catalanization, there are many young people who understand Catalan, though it still remains an incomprehensible foreign language for the majority of islanders).

Thence the importance of Semantics, not only for the comprehension of isolated words, but also, as we have just seen, for the aprehension of their meaning in context.

Let us see some more semantic examples:

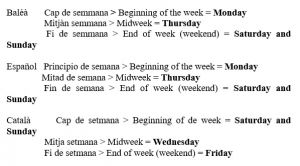

Parts of the day: semantic system

BALÉÀ

Sa dematinada from 3 a.m. to 6 a.m. dawn, small hours.

Es dematí from 6 a.m. to 12 a.m. morning.

Es mitjdía from 12 a.m. to15 p.m. noon.

S’hòrabaxa from 15 p.m. to18 p.m. afternoon.

Es decapvespre from 18 p.m.to 21 p.m. evening.

Es vespre from 21 p.m. to 24 p.m. towards the night

Sa nit from 24 p.m. to 3 a.m. night

(seven meanings)

ESPAÑOL

La madrugada from 24 p.m. to 6 a.m. dawn, small hours.

La mañana from 6 a.m. to 12 a.m. morning.

El mediodía from 12 a.m. to 14 p.m. noon.

La tarde from 14 p.m. to 21 p.m. afternoon-evening.

La noche from 21 p.m. to 24 p.m. night.

(five meanings)

CATALÀ

La matinada from 3 a.m. to 6 a.m. dawn, small hours.

El matí from 6 a.m. to 12 a.m. morning.

El migdia from 12 a.m. to 15 p.m. noon.

La tarda from 15 p.m. to 21 p.m. afternoon-evening.

La nit from 21 p.m. to 3 a.m. night.

(five meanings)

Parts of the week: semantic system

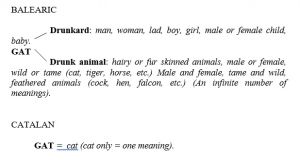

Semantic system of the word GAT (drunk)

Of the word MISSATJE

BALEARIC > Missatje: A young, mature, or middle-aged or old person who works as a farmhand or go-between in a mansion, palace, farm, shop, etc. (an infinite number of meanings).

CATALAN >Missatje: message (message only = one meaning).

of the word MITJÀ

BALEARIC > Mitjà: limestone 5cms, 10 cms, 15 cms, 20cms, or 30cms. Thick; of king´s foot; of emperor, etc. (as many meanings as its measures).

CATALAN > Mitjà: medium; mean(s) of; resources. (Three meanings).

Different use of gender

In the given examples, it is noticeable that the Spanish and the Balearic use the feminine article with feminine nouns, whilst in Catalan the masculine article is used with those feminine nouns.

From the above mentioned philological samples of a comparison between the Spanish, Balearic and Catalan languages, it is clear that they are three different languages, although undoubtedly branches of a common tree. In which comparison, however, we detect more philological similarities between the Spanish and the Catalan than between the Balearic and the Spanish. With the exception of the phonetic field, though not so in the phonologic system.

Being the Balearic such an archaic language; which amounts to say, being it a Neolatin language that has survived until the XXth century, which makes it more than a thousand years old, we should not permit it to disappear and be supplanted by the Catalan through the linguistic immersion that has in fact been taking place in the Balearic Islands since 1983 as a result of a politician´s whim. (See page 4).

I think it is time to set the record straight in The Balearic Islands, both from a historical and a linguistic point of view, as it is also time that our politicians give up outdated imperialistic approaches.

We have proved that the History of the Balearic Islands, or at least most of it, is not what we have been told by those historians who were supposed to be invested with a certain baggage of objectivity and scientific methodological rigour. However, it is clear that any type of investigation entails the possession of great patience. And that patience is scarce among our modern scholarly historians.

But in spite of all that, one must not conclude that the philologists and the National-Catalanist linguists adopt a different approach from that of the historians; in fact, whenever they are told that the Balearic is a different language (different from the Catalan), they reply that “This is a theory opposed to the scientific truth accepted by everybody”. (Diario de Mallorca. Linguistic Standardization Campaign. Ana Moll, 21-9-1992) (A declaration that takes place some long 12 years after the XVlth Romanic Philology and Linguistic International Congress).

Another declaration came from doña María Barceló, Doctor of History, who stated that “Those who deny the Catalan roots of our culture simply do that due to their ignorance or with a wicked intention” (Diario Baleares. Mallorca en Baleares. September 19, 1990. Palma).

And we finish this series of drastic comments with the words of Carme Riera, Fiction National Prize (El día del Mundo, Cultura, December 1995), who (15 years after the above mentioned Congress) said: “I think it is absurd to question the unity of the Catalan language, and those who question it do not have their feet on the ground”.

However, we dare say that in this essay we have proved such statements to be false and distorted, and we shall validate our opinion with the following facts.

The 16th Romance Philology and Linguistics International Congress

The 16th Romance Philology and Linguistics International Congress took place in Majorca from the 7th to the 12th of April 1980. It was sponsored by the “SOCIÉTÉ DE LINGUISTIQUE ROMANE”, and organized by the “Cátedra Ramón Llull” of the University of Barcelona and the “Estudi General Lul.lià” of Palma. A document was presented for the signature of the 723 congressmen from all over the world, in which it was said that the undersigned were opposed to the linguistic maneuvers of cessation of the Catalan language in Valencia with arguments devoid of any scientific foundation.

Well, only 36 congressmen signed it.

(sic) DOCUMENT

Les romanistes soussignés, participant au XVI Congrès International de Linguistique et Philologie romanes, manifestent leur satisfaction des progrès récemment obtenus par la langue catalane sur la voie de la normalisation avec la création de nouveaux centres de recherche, l’incorparation de la langue aux divers degrés de l’enseignement, la multiplication des publications et autres manifestations culturelles, bien que l’on n’atteigne pas encore les moyens de communication social avec l’intensité souhaitable. Nous regrettons, néanmoins, les tentatives de sécession idiomatique effectuées au Pays Valencien par certains groupes de presion pour des raisons dépourvues de tout fondement scientifique. Le catalán, comme n’importe quelle langue, a sa propre structure; bien définie, et les romanistes de ce XVI Congrès considèrent comme inacceptables ces tentatives de fragmentation linguistique.

Majorque, avril 1980

(Translation) DOCUMENT

The undersigned Romance language Specialists attending the 16th Romance Philology and Linguistic International Congress, manifest their content with the progress lately made by the Catalan language through its Standardization, with the creation of new investigation centres, the presence of the language at the different levels of teaching syllabuses, the variety of publications and other cultural manifestations, although it has not reached the desired level of intensity in the means of social communication (mass media). On the other hand, we regret the linguistic secession attempt by certain pressure groups in the Valencian Country, whose reasons cannot be based on any scientific grounds. The Catalan has its own, well defined structure as a language, and the Romance specialists attending this 16th Congress see those linguistic fragmentation attempts as unacceptable.

Majorca, April 1980.

Signatories: Iorgu Iordan (Bucarest). Max Pfister (Saarbrücken). Giuseppe Tavani (Roma). Veiko Väänänen (Helsinki). Eugenio Coseriu (Tübingen). Isaac Salum (Säo Paulo). Max W. Wheeler (Liverpool). Pierre Bec (Poitiers). Mario Wandruszka (Salzburg). Herber Peter (Viena). Helmut Lüdtke (Kiel). Luis F. Lindley Cintra (Lisboa). Artur Greive (Köln). Celso Ferreira da Cunha (Rio de Janeiro). Udo I. Figge (Bochum). Madeleine Tyssens (Liège). Brigitte Schelieben-Lange (Frankfurt). Giuliano Gasca Queirazza (Torino). Manuel de Paiva Boléo (Coimbra). Gaston Dulong (Québec). Giuseppe Grilli (Napoli). Maria Grossmann (Cosenza). Xavier Ravier (Toulouse). Cesare Segre (Pavia). Sofia Kantor (Jerusalem). Michael Metzeltin (Groningen). Félix Lecoy (Paris). Georges Straka (Strasbourg). Kurt Baldinger (Heidelberg). Gerold Hilty (Zürich). Alberto Vérvaro (Napoli). Georg Kremnitz (Münster). Kristin A. Müller (Salzburg). Alberto Limentani (Padova). Albert Henry (Bruxelles). Aimo Sakari (Finlandia).

A total of 36 (thirty-six) signatories; which means that only 36 scientists agreed on the text of the document. And what was more meaningful, from the group of the Scientific Committee itself, only 7 (seven) signed the document.

Which means that what the national-Catalanists call “All the scientific world” is in fact reduced to only 36 scientists.

Then those who really represent the absolute majority of the Romance scientific world, if not the totality, the 687 remaining scientists, once they have not accepted the unacceptable national-Catalanist theories, they do not count, as if they had never existed, as if they had never attended the Congress. Odd...Isn´t it?

However, in the year 2003, 23 years after that Congress, they still maintain that “to deny the unity of the Catalan language amounts to being against the opinion of all the scientific world”.

And if they are told that only 36 sientists accept that “all”, (Balearic, Valencian and Catalan) is the same language, they reply that “None of the others has made a negative declaration”.

So the question arises: What answer can there be to the reasoning of minds so acute?...

You are kindly invited to think of an appropriate answer, for such display of eloquence has rendered us astounded and speechless.

However, we came to the conclusion that from a linguistic as well as from a historical approach, the Balearic language is not, neither has it ever been, a dialect of the Catalan language.

1 and 2. Book of Minutes of the 16th Romance Philology and Linguistic International Congress. Editorial Moll. Palma 1982.

BALEARIC, ROMANCE LANGUAGE

It is very curious to observe that in all textbooks when the origin of the pre-Roman, neo-Latin or Romance Languages is studied, no mention at all is ever made of the language originally spoken in the Mallorca Kingdom. We can find references to the Tartesian language spoken in western Andalucía and southern Portugal. We can find references to the Iberic language spoken in eastern Andalucía, eastern coast of Spain (present Valencia) and Ebro valley. References to the Basc language spoken in the Basc country and south-west of France. References to the Celtiberic language spoken in Burgos, Logroño, Navarra, Soria, Guadalajara, western Zaragoza and Teruel. Reference to the Visigothic language etc, etc. However nothing is mentioned about the original language spoken in the Balearic Islands; as if it had never previously existed, as if the Balearic Islands had always been uninhabited before the arrival of the Muslims in the 10th century. Not ceasing to be even more curious to observe how linguists of all time, have accepted the theory that the speech of the inhabitants of the Balearic Islands dates back to 1229, with the conquest of the Kingdom of Mallorca by Jaime I de Aragón which dogma of faith. But, however, Archaeology, Ethnology, us forward towards a permanent population since at least 1200 BC without interruption. However, just taking for reference the Classical Historiography we must undoubtedly proclaim some evident statements: that some kind of language was spoken by the famous Balearic slingshotters when they were so deeply praised as being excellent fighters by Anibal or Julius Caesar, among others.

The purpose of the present article is to prove the existence of the original Balearic language, clearly differenced from any other, and to give a full account of its existence through diacronic.

Therefore, without going into analyzing the evolutionary process of the human species, it is quite true that the person from birth has the gift of words, through which they communicate with their peers and order the world that surrounds them. And as a result of the daily use of that language over many centuries, which at first were nothing more than a more or less extensive vocabulary, is enriched by the creation of its structure with words that do not vary when it comes to constructing sentences. spoiled. And that structure, the more isolated it is over time, the less changes it will experience, staying closer to its roots.

The linguistic evolution of European languages has always been studied from the perspective of terrestrial migrations with its Indo-European linguistic background; not taking into account at all, the migrations of speakers in Semitic languages, which, expanding by sea, settled on almost the entire Mediterranean coast. Doing it in the Balearic Islands in 1200 BC. (Juan Dameto, Vicente Mut - 1840), fifty years after the fall of Troy before the Achaeans; of Mycenae and Knossos before the Peoples of the Sea, and 800 years before the creation of Rome.

For this reason, we can assure you that the history of the Balearic language does not begin with the conquest of the kingdom of Mallorca by Jaime I of Aragon, Count of Barcelona and Lord of Montpellier, as we have been assured for too many years, since all the Catalan History and Language Departments. Therefore, we must ask ourselves the following question: Where did the first and successive inhabitants of the Balearic Islands come from?

The answer is simple if we look at the migratory movements during the Ancient Age; where the great migrations have always come from, from the Levant. From there they arrived by sea by the route known as the route of the islands, the builders of buildings of a cyclopean character, who, coming from the Middle East, passed through Turkey, Greece, southern and central Italy, Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia, the Balearic Islands, south, west and north of the Iberian Peninsula, reaching the Casitérides Islands and Denmark, leaving their culture and language beyond that, since in all those places there were significant settlements (Javier Aramburu-Zabala, 1994 p.17). These cyclopean constructions are called in the Balearic Islands "talayot" [tɵlɵjɒt]. Word is of Iberian origin. Well, having been shown that Basque (Euskera) is the evolution of the old Iberian, as described by Jorge Alonso (1996), we find in that language (Euskera) the word "talaia" [ta'laia] which means guard post . And with the same semantics we find it in the Balearic language: talaya [tɵ'laʝɵ]. Being «talayot» [tɵlɵʝɒt] a derivative of the first, since the suffix morpheme –ot [ɒt] in Balearic is an augmentative / derogatory:

Homonot [omonɒt]: big and ungraceful man.

Cotxot [kot͡ʃɒt]: larger-than-normal vehicle and exaggerated lines.

Talayot [tɵlɵjɒt]: watchtower of great proportions and very rough construction.

From what language was the speech of the Talayotics derived then? It is not known with certainty, since only several women's names have been found by inscriptions found on tombstones from Roman times, and with Latin spelling, since as is known the Balearic slingers were handwritten, whose meaning or linguistic relationship has not yet been possible. be established with exactness, as far as possible that its roots are Indo-European, although they have been dated as proper names of the Talayotic culture, as indicated by Javier Aramburu, Carlos Garrido and Vicens Sastre, (1994, p.24). These are: Cucuma, Cuduniu, Isaptu, Norisus. Likewise, there is another relationship with proper names, also taken from Roman tables and funeral inscriptions, whose linguistic affiliation is also not clear (Javier Aramburu, 2007 pp. 175-192. Cristóbal Veny, CSIC 1965): Aspro, Cloi, Clodia, Paditu , Uniuis.

We also find in the toponymy and in Balearic speech the suffixes: -itx, -utx, -itxol, -utxol, [-it͡ʃ, -ut͡ʃ, -it͡ʃɒl, -ut͡ʃɒl]. Of which we have not yet found any linguistic affiliation, (since Arabic uses -txí: Marratxí = the one who is from Marrakech). Which give us a filiation of membership or relationship with respect to the root. And so we have for example:

With the suffix -utx:

Fornalutx [foɽnɵ'lut͡ʃ] > relative to the forge or place of forges.

Ferrutx [fɵ'rut͡ʃ] > relative to iron or iron place.

Artrutx [ɵɽ'tɽut͡ʃ] > relative to Arta (Greek population).

Porrorutx [porο'ɽut͡ʃ] > relative to the leek or place of leeks.

With the suffix -itx:

Andraitx [ɵn'dɽɑjt͡ʃ] > those of Andros (Greece).

Balitx [bɵ'lit͡ʃ] > those of Baal (Phoenician god).

Costitx [cos'tit͡ʃ] > those on the coast.

Castellitx [cɵstɵ'ʎit͡ʃ] > those of the castle.

Felanitx [fɵlɵ'nit͡ʃ] > those of the Felan clan. Or also: place of wolves.

Favàritx [fɵ'vɑɽit͡ʃ] > those of Favara (Sicily).

Fartàritx[fɵr'tɑɽit͡ʃ] > those of Farta (Ethiopia).

The minor toponym Felanitx has two meanings of the same linguistic root. For felan comes from the proto-Germanic "folijana"; which we find in Old High German as "fuolen" with the meaning of: caress; which when passing to the Celtic languages as "faol" modified its meaning to that of: wolf; and as a diminutive derivative: "faolain" which means wolf cub. A clan by the name of Felan is documented in the history of Ireland in 300 AD (Nora Kershaw, 1970). So it is not at all unreasonable to think that Celts with that name and contemporaries of our Balearic slingers, having served together in the armies of Rome, settled and settled in what is now the town of Felan (-itx) on the island of Majorca.